In the weeks leading up to the 2012 Presidential election it was nearly impossible to not hear the name Nate Silver. His projections of the election came to dominate the news cycle and he himself became the subject of the media zeitgeist. Silver was either lambasted as a charlatan by those who disagreed with his lean towards an Obama win; or he was heralded as a genius by liberals whose fear of a Romney victory he assuaged. This backdrop was the perfect setting to be reading Silver’s first book The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-but Some Don’t. The narrative in the book described a far different world of projection and probabilistic thinking then what was occurring in the media in the lead up to the election.

The heart of the book lies in a relatively simple proclamation in the Introduction: “It is a study of why some predictions succeed and why some fail.” It is from this starting point where Silver launches an erudite tour of forecasting and predictions. The book outlines successes, such as his own contribution to the sabermetric trends in baseball with his PECOTA system and the advances that have been made in weather forecasting in the age of computers, however, the real meat of the book focuses on the failures of prediction, such as in our economy or in predicting earthquakes. It is here that Silver examines the questions of why we failed in certain predictions but also, more importantly, is it ever possible to predict certain phenomena?

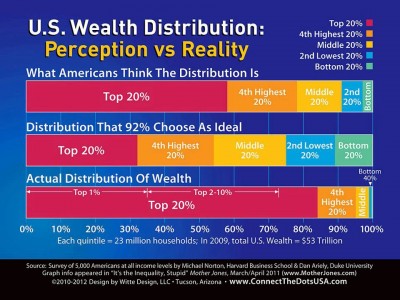

Silver breaks down the failures of prediction (it’s here that I want to note that Silver makes a distinction between prediction and forecast, but for purposes of this review I will use both loosely) into two spheres. First, there’s the human element which acknowledges that “your subjective perceptions of the world are approximations of the truth.” This is what makes it so damn hard to separate the signal from the noise, especially in a world where data grows almost exponentially. As Silver points out, nature’s laws don’t change, yet our ability to filter the data is hindered by our biases. Second, some systems are dynamic and/or irreducibly complex, whereas it may not be random, it may be unpredictable because of complexity. Silver explores this idea in his fifth chapter on earthquakes.

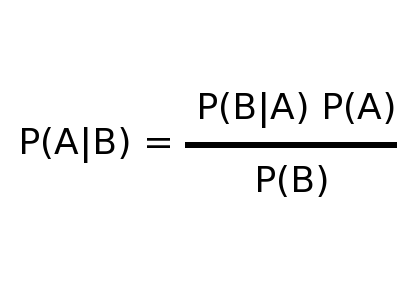

Understanding and acknowledging our limits and failures in forecasting however does not preclude us from trying to improve our forecasts. The eighth chapter of The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-but Some Don’t is the worth the price of the book, as it breaks down Bayes Theorem and Bayesian thinking into a layman’s terms. Through the backdrop of a professional NBA gambler, Silver takes the reader through a well written explanation of how Bayesian theory is becoming the preferred method in the scientific community for evaluating hypotheses, over taking the Frequentist method. Clearly Silver is an advocate of Bayesian thinking, as he shows its applicability and strengths throughout the remainder of the book.

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-but Some Don’t is an entertaining and lucid exploration of the world of forecasting and predictions. There’s a fine line between humility and confidence in when facing uncertainty, one must have faith in his prediction and methodology but understand that many have failed greatly by being overconfident. That being said, I’m willing to go out on a limb and bet that at least 68% of the readers of PoliticalBooks.org will enjoy this book and ought to give it a read.